Blog Archives

The Sting Of Memory

THE STING OF MEMORY

FRANK MCCOURT, AUTHOR OF “ANGELA’S ASHES,” IS BEING HONORED IN HIS HOMETOWN OF LIMERICK. BUT SOME LOCALS HAVE THEIR IRISH UP ABOUT MCCOURT’S RECOLLECTION OF GRINDING POVERTY IN THE CITY’S “LANES.”

By Fawn Vrazo

The Philadelphia Inquirer November 4, 1997

LIMERICK, IRELAND: Frank McCourt is back in Limerick, the city whose poverty he depicted so vividly in his best-selling memoir Angela’s Ashes. It has not been the easiest of homecomings.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author cried last week on the stage at the beautiful new Limerick University. He was both overwhelmed and in a state of disbelief: The poor kid from Limerick’s slums was wearing a cap and gown, receiving an honorary doctorate as the city’s highest officials applauded him.

“It was very hard to get through that,” McCourt said after the ceremony.

The return home, which has McCourt staying in Limerick for two weeks as writer-in-residence at the university, has been difficult in other ways as well.

Around this west Ireland city, there are those who love Angela’s Ashes and those who hate Angela’s Ashes and many who love it but feel its compelling tale of excruciating Limerick hardship in the 1930s and ’40s was an exaggeration that goes somewhat beyond the truth.

McCourt has come in for criticism and re-evaluation here, and not only from boosters whose civic pride has been wounded by his searing recollections of dying babies, starving children and cruelly indifferent neighbors and kin.

“It’s good, but it isn’t all right. You know it was overdone,” said Eric Lynch, who grew up with McCourt on the poor “lanes” of Limerick and was a classmate with him at the Leamy National School. “But that’s what a writer does,” added Lynch, who remains a close friend.

The book’s “forensic evidence, so to speak, doesn’t add up,” said Jimmy Woulfe, deputy editor of the Limerick Leader newspaper. Still, Woulfe added, that should not “cloud the reality this was a magnificent piece of literature.”

Not all of the criticism has been that polite. One Limerick resident, Paddy Malone, a childhood friend of McCourt’s actor-brother Malachy McCourt, ripped the book into five pieces and threw it on the floor in front of McCourt when the author was here last summer for a book signing.

More recently, threatening letters were received by Limerick University officials after they announced their plans to honor McCourt. Extra security – in the form of two beefy security guards in plaid sport coats – was in evidence last Tuesday when McCourt received his honorary degree.

McCourt dismisses the book’s criticisms with firm scorn.

The complaints are “peripheral,” he said last week. “It has nothing to do with me. You write a book, and that’s it. It’s gone.”

But the 67-year-old McCourt, a longtime New York high school teacher with white hair and a pale, delicate face, concedes that Angela’s Ashes is “a memoir, not an exact history.”

“I’m not qualified to do that,” he told the audience at his doctoral degree ceremony.

He has admitted one error. In the book, childhood classmate Willie Harold is depicted walking to his first confession while “whispering about his big sin, that he looked at his sister’s naked body.’

‘ The problem was that Harold did not have a sister, and last year the by-then aging and cancer-ridden Harold approached McCourt at a book-signing event to point out the mistake.

“I settled that with him,” McCourt said last week. “[Harold] said, `I’m in bad shape, I don’t have any money, could you give me a book?’ ” Of course, said McCourt, and he did. If McCourt thought this was in any way an inadequate gesture to a sick, wronged friend, he did not indicate it. Harold has since died.

Chief among the contentions of critics here is that McCourt simply could not have had as poor a childhood as his book relates.

In a famous opening passage of Angela’s Ashes, which won the 1997 Pulitzer Prize for biography, McCourt writes: “When I look back on my childhood I wonder how I survived at all. It was, of course, a miserable childhood: the happy childhood is hardly wort h your while. Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood.”

In the 426 pages that follow, McCourt describes a childhood of harrowing destitution. The chief cause is the alcoholism of his father, Malachy McCourt, a Catholic from Northern Ireland who settled in Limerick with his wife and McCourt’s mother, the former Angela Sheehan of Limerick, after the McCourts moved to Ireland in the 1930s from New York.

While Malachy drinks away the family’s few dollars or pounds, a despairing Angela huddles in a bed or dazedly smokes cigarette after cigarette. McCourt’s beloved and weak baby sister, Margaret, dies at seven weeks in New York; his twin brothers Eugene and Oliver die from apparent pneumonia as toddlers in Limerick; McCourt himself nearly dies of typhoid fever; his first young lover, a Limerick girl, dies from the tuberculosis that is raging through the city at the time.

The McCourt children survive on sugar water, soured milk, boiled pigs’ heads and occasional handouts from relatives and shopkeepers, while confronting bone-chilling winter cold and attacks of bed fleas. In school, McCourt and his classmates, some of whom go shoeless in the winter, are beaten relentlessl y with canes by their teachers.

Reviewers swooned when the book was released, and readers worldwide have kept Angela’s Ashes at the top of best-seller lists for more than a year. “Outstanding . . . a bittersweet and grimly comic narrative of growing up dirt-poor in rain-sodden, priest-ridden Limerick,” wrote reviewer Boyd Tonkin of the New Statesman.

But was it really that bad? Gerard Hannan, a Limerick bookstore owner and radio broadcaster who has written a rebuttal to McCourt’s book, says that McCourt created “sort of an illusion of Limerick” that ignores the fact that the people of the city’s impoverished lanes on the north side of town banded together to share food and give each other support. “I felt he totally ignored the sense of community among the people,” said Hannan. Hannan’s own credibility is being questioned in Limerick, though, since his rebuttal book is called Ashes and has become quite a local best-seller by riding on the coattails of Angela’s Ashes’ success. But criticism of McCour t’s book is being raised by others as well. “Is this the picture of misery in the Lanes?” said a Page One headline last week in the Limerick Leader. Beneath it, there was a picture of McCourt in the 1940s, smiling broadly and wearing the neat uniform of the St. Joseph’s Boy Scout Troop.

McCourt does not mention in his book that he was in the Boy Scouts, local critics note, nor does he explain how his poverty-stricken mother, now deceased, still found money to send him to Irish dancing lessons, and to buy packs and packs of cigarettes.

His now-deceased father, Malachy, is depicted in the book as being scorned by local employers because of his Northern Ireland accent. But in fact he was given what were considered then to be prime jobs at the city’s cement factory and flour mill, Leader editor Woulfe observed. McCourt does write about those jobs in his book, noting that his father lost both of them because of drinking.

“Most people would salute the [university’s] acknowledgment of Frank McCourt while some of his peers who live in the lanes dispute the level of poverty – he seems to be just one of the boys,” said Woulfe. The Leader, though, has strongly supported Angela’s Ashes in editorials.

McCourt said in an interview that not only was his childhood as hard as his book says, “it was harder. It was harder. My brother [the younger Malachy] said I pulled my punches. I was moderate. And who would know? How can you tell another person’s [life], especially with an alcoholic father and a mother worn out from child-bearing?”

Appearing Wednesday at a creative writing workshop sponsored by the university, McCourt observed that his book is a memoir, “and a memoir is your impressions of your life, and that’s what I did. There are facts in there, but I excluded other things.”

Among things excluded from the book, said McCourt in an interview, were accounts of sexual abuse by a local priest. McCourt alluded, without elaboration, to himself and other Limerick boys being “interfered with, as they say” by a priest returning from an overseas mission.

But “I didn’t want to write that,” said McCourt, “because it’s standard now” to blame one’s adult problems on having been sexually abused.

McCourt bears no ill will toward Limerick, a city he describes as “beautiful.” He said he plans to help both the university’s outreach program to the children’s poor and the local St. Vincent de Paul Society, which rescued the poor young McCourts many times with handouts of clothes and furniture and food.

But as for the criticism of Angela’s Ashes, McCourt said, it’s just “all kinds of sniping. I think nothing of it.”

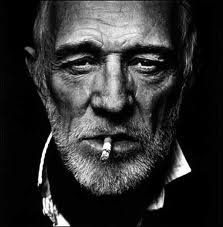

Richard Harris On McCourt And Angela’s Ashes

Richard Harris Stands Up For His Native City in Local Radio Interview

By Eugene Phelan

Airdate January 20th 2000

International film star Richard Harris has publicly lambasted his fellow Limerickman and contemporary Frank McCourt for his depiction of Limerick in the Pulitzer Prize winning book ANGELA’S ASHES.

He also launched an attack on film director ALAN PARKER whom he accuses of using Limerick as a ‘whipping boy’ to generate publicity for a twenty million-dollar flop.

In a frank two-hour live interview on the Limerick airwaves with Ireland’s most vocal McCourt critic Gerry Hannan, who presents a nighttime phone-in show on RLO, Harris spoke out for the first time on what he describes as a bitter attack on his native city.

Harris highlighted the fact that McCourt recently told the American media that the film star came from a different more up market part of Limerick than he did and couldn’t possible know about poverty and hardship on the lanes of Limerick.

‘But McCourt was very well versed in telling the press how well I lived. If he is so well informed about my life why is it unnecessary for me to be informed about his life?’

‘I knew Frank in his New York days and I found him to be probably the ugliest and the most bitter human being I have ever met in my entire life.

Frank was full of bitterness.

I don’t think I ever confronted a man that was so angry.

Ever fibre of his being was in rebellion against something.

I believe that he hated me with a passion because according to him I came from an elitist part of Limerick and because I became so successful.

Though he would use my success to promote himself he very much resented my success.

If Limerick is, as he claims, a city of begrudgers why then they did they give him an Honorary Doctorate at the University of Limerick and why did the Mayor propose making him a Freeman of Limerick?

Are these the acts of begrudgers?

I was offered an Honorary Doctorate by UL and though I never say never I would have to think very seriously about it because I don’t want to link myself to totally mediocre non-entities like McCourt.

So why does Harris believe that McCourt hates Limerick?

‘I really don’t know. I agree that there are stories about Limerick in ANGELA’S ASHES that just don’t make sense. Of course I knew that the poverty was going on but I also knew many people with difficult lives who grew up on the lanes of Limerick but yet, even to this day, there isn’t one ounce of bitterness in them.

There is a friendly tribal rivalry which exists in the rugby world in Limerick but when an outside team comes in to play they all come together in unison to support their own.

It is for that very reason that Limerick is unique.

The loyalty is absolutely astonishing and, I believe, that that element of Limerick totally by-passed the McCourts.

They are devoid of any sense of loyalty and are filled with hate for Limerick.

Here is a simple question.

Why wouldn’t Frank and Malachy McCourt hate Limerick – the fact is they hate each other.

Frank came out in a big campaign recently and knocked Malachy’s book.

When he was asked did he read Malachy’s book he said he wouldn’t read it.

He is quoted in some American newspapers as asking why Malachy dared to impose himself on my terrain.

They couldn’t even support each other.

Then Malachy came out and was vicious about Frank.

I’ve heard that Frank thinks of himself as a literary genius but I think his book has no literary merit whatsoever.

Recently the London Times carried an article about the terrible decline in the arts in the last century and it finished by saying that we started the last century with Henry James and we ended with Frank McCourt.

Harris laughs and says that he cannot think of anything more insulting.

But what about the Pulitzer Prize surely that is a real claim to fame?

‘Winning the Pulitzer is not that big a deal. I have seen hundreds of plays that have won the prize and you couldn’t sit half way through it. The Pulitzer is a common prize that means very little.

I was talking to Brian Friel recently who told me that there is not even one single line of poetry or literary merit in the book.

I asked Brian to explain to me why this book won the prize.

He believes that at the moment in America the fact that you are Irish is very fashionable and ANGELA’S ASHES, being Irish, is riding on this wave of enthusiasm for all things Irish.

Brian told me that if that attitude continues then the ANGELA’S ASHES of this world would deplete that opinion about Ireland.

A Coward Act

‘I first met Frank McCourt years ago in his brother Malachy’s pub called ‘Himself’ in New York and he was very derogative and derisive in his attitude and remarks about Limerick.

I was in discussion about Limerick to Malachy when Frank raised his fist and hit me a terrible belt on the nose. Like a hare running from a hound he raced toward the exit door and ran out of the pub. I said to Malachy, I’m afraid your brother is not really a Limerickman. When Malachy asked why not I told him that I have never yet been confronted by a Limerickman who ran away from a fight.’

We don’t do that in Limerick we stand our ground and we fight.

To run from a fight is not part of the Limerick character at all.’

‘I knew Malachy for years and he wrote a book called A MONK SWIMMING and I am very heavily featured throughout the book. I found both Malachy and Frank to be absolute users. They would use me and my position in America for them to gain some kind of notoriety and I can best characterise them both as users.

Angela’s Will to Die

‘I also knew Angela McCourt quite well and I visited her regularly and I spent a lot of time with her and they treated her really badly.

The way they spoke about their mother made me very angry.

They had an obvious disdain for their mother and I remember on one occasion in the pub where I grabbed her son Malachy by the neck and shouted that she is your mother and you cannot treat her like this.

Malachy’s only answer to me was that they were bringing her lots of beer and cigarettes in the hope that she would die because she is costing us rent money.

I believe in my heart that they were willing a death.

I found that very offensive to such an extent that I threatened to kill him.

‘When I met Angela she was in her old age and she was very quiet and once when I was alone with her she told me that she knew that they didn’t like her and wanted her dead.

She said that they don’t like me Dickie, they don’t treat me well, they don’t want me to be here, I am a nuisance to them and I am no more than a rock around their neck.

Angela told Richard that the boys treated her so badly that she wished she were dead and gone.

The Mystery of Angela’s Ashes

When Angela McCourt died she wanted to be buried in Limerick.

I happen to know that there is an Irish travel agency in New York where Malachy and Frank went to book tickets to take the coffin back to Limerick.

But the boys refused to pay the extra charge for the coffin.

So they decided to cremate their mother who allowed them to put her ashes into their overnight bags and take her back for nothing.

Now I know that Angela was a very devout Catholic and she would not have wanted to be cremated. Being cremated was something that she couldn’t countenance at all and she wanted to be buried.

But the boys were not willing to pay for that so they cremated her and put her into a tin.

When they got to the Airport in New York Frank turned to Malachy and asked ‘have you got her?’ and Malachy replied ‘Got who?’

They argued for a while and realised that the ashes had to be in one of the bags but neither one known which bag exactly.

The boys had to take separate flights for one reason or another and Malachy’s, who believed he had the ashes, plane got into trouble and had to go back to New York.

In all the coming and going the bags, containing the ashes, got lost.

It is a commonly held opinion amongst the Irish in New York that Angela’s Ashes are, in fact, buried away in some far distant remote lost property corner of Kennedy Airport in New York.

Limerick Loyalty

Speaking about Limerick’s influence on Frank McCourt – Harris believes that it is obvious that the author did not experience the true spirit of the city. ‘Limerick is a sporting city and when, as a young man, I had TB legions of my mates from the Young Munster’s Rugby Club of which I am a life time member came to see me in my sick bed. These guys were from the same background as the McCourts, they came from the lanes of Limerick and they had just as tough a time but, in spite of the poverty and hardship, they had an almost indestructible loyalty to Limerick.

You never heard from them one condemnation about Limerick. Not even one utterance of disloyalty and this was a quality that Frank never inherited.

Limerick people have passion about each other.

When I go back to Limerick they will attack me and they will make fun of me and they will pass jokes about me.

‘But God help if somebody from Dublin or London said anything nasty to a Limerickman about me – they would end up being killed.

‘Now that kind of loyalty is something that McCourt just did not have.

‘When Malachy McCourt played rugby he didn’t play with his own people. He didn’t play with Young Munster’s, St. Mary’s or Presentation, which was the clubs around his area. Instead he played for Bohemians and in those days they were the snobs, the most right wing club in Limerick.

Malachy elected not to play with his own class but to upgrade himself and play for Bohemians.

The man seems to be on a lifelong crusade to upgrade himself.

‘I believe that Malachy has always had ambitions above his station.

Alan Parker’s Agenda

We must remember that Hollywood is bereft of good material at the moment, all these remakes are getting tedious, ANGELA’S ASHES is such a worldwide phenomenon that it’s success was almost guaranteed.

But now that success seems highly unlikely.

Now it seems the only way to retrieve some of the investment is to create as much publicity as possible.

Alan Parker has come out in the past few days in a wealth of very bad publicity about Limerick.

He has been saying that Limerick is backward, uneducated and claiming that he got no cooperation whatsoever with the making of the movie.

He is accusing the people of Limerick of being catholic bigots.

All this negative publicity about Limerick is just a Hollywood publicity stunt to create interest in the film.

I believe that PARAMOUNT PICTURES know full well that this picture is not going to make it. It was test screened in America recently and the public reaction to it is very poor. Now they know they are into a twenty million-dollar loss here and they are drumming up as much bad publicity as they can to get people to come to the movie.

What they have done is they have picked Limerick as the whipping boy.

I have made 63 movies and I know how these guys operate.

I know exactly what they are doing and what they all about.

Alan Parker hasn’t directed a good movie in years, he destroyed EVITA, which went down the tubes for over one hundred million dollars, and he hoped that this was his chance to make a success.

The book was so successful and he hoped to ride on the coattails of the book but when he found out on screening tests that the movie is not going to make it his PR people, led by him, tried to create this huge publicity stunt just to get press.

‘They asked me a long time ago to come out and help them to create press but I refused because all I am doing is publicizing your picture.

That was my feeling until Parker came out and singled out Limerick for alleged prejudices, lack of education and so on. He even made the most stupid comment I ever heard in my life when he said that they are so backward in Limerick that they don’t even have EASTENDERS.

Can you imagine a man of culture making such a remark?

The man must have been mad to say it.

When I heard this I said to myself that this is it I have got to defend my city.

‘I am the man who should defend it, I love Limerick, although we have our bouts of hate and love this man has no right to make such ugly remarks and I will stand up against him and defend it now.

The portfolio that Alan Parker has given himself to try and create publicity for his movie at the expense of Limerick is totally unacceptable to me.

Angela’s Movie

‘I saw ANGELA’S ASHES this week and I think the only Oscar it deserves is for special rain effects. The movie is two and half-hours of rain.

Parker has taken the Limerick of that era and he has dated it back to the late 19th Century.

It is more Dickensian in its squalor than it is accurately Limerick.

‘If so much rain fell in Limerick we would be famous for our water polo teams.’

I felt that, for the people not from Limerick, the book is a thrashey ‘unputdownable’ read but with the movie you can’t wait to get out.

It is a boring, dull and very repetitive movie and is totally unmoving.

I admit that McCourt had a wonderful sense of humor, an ironic sense of humor, which is characteristic of most Limerick people but I found that the picture does not have one bit of it.

The movie is nothing short of a two hour moan and the book was one long moan and ‘Tis is even worse.

The movie is one long perpetual moan.

It like McCourt is screaming out for love.

‘Feel sorry for me, love me, an endless search for love.

But I doubt very much that if he finds this elusive love that he can reciprocate.

I don’t think he can give anything back, it’s too late, not when you can treat your mother like that, what does his treatment of his mother in the book tell you about his emotional condition?

I don’t think all the money he has made by tarnishing the good names of people who cannot defend themselves against him will give him a moment of happiness or will fill that hollow in his life.

Source:

A Miserable Liar?

Rarely has a book had such a compelling opening line. ‘When I look back on my childhood I wonder how I survived at all. It was, of course, a miserable childhood: the happy childhood is hardly worth your while. Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood.’

And so Frank McCourt, who died on Sunday aged 78 after a battle with skin cancer, launched a new literary genre: the misery memoir. Dozens have followed him – so much so that they are now generically called ‘mis-lit’. These tales of childhood woe have become highly lucrative.

Called ‘inspirational memoirs’ by publishers, ‘mis-lit’ now accounts for nine per cent of the British book market, shifting 1.9 million copies a year and generating £24 million of revenue. HarperCollins recently admitted to a 31 per cent increase in annual profits thanks to ‘mis-lit’.

But as well as starting a publishing phenomenon, McCourt’s searing bestseller Angela’s Ashes, which has sold some five million copies, also began a terrible feud.

Locals called him ‘a conman and a hoaxer’, and claim he ‘prostituted’ his own mother in his quest for literary stardom, by turning her into a downtrodden harlot who committed incest in his book.

One thing is not under debate – when it came to writing limpid, magical prose, McCourt was the real thing, following in his countrymen’s footsteps to emerge as an Irish writer par excellence.

So just who was the real Frank McCourt? Did he win the Pulitzer Prize with his lyrical, poignant memoir under false pretences? Or was he indeed the ultimate rags-to-riches story, who survived the grinding poverty of Limerick’s slums to rise like a phoenix from the ashes, triumphant?

The truth is, we may never know. Perhaps, as McCourt did in Angela’s Ashes, we had better begin at the beginning. In the book, set in the Thirties, McCourt writes that his parents returned when he was four from New York to Ireland, against the tide of Irish emigration.

His family consisted of ‘my brother, Malachy, three, the twins, Oliver and Eugene, barely one, and my sister, Margaret, dead and gone’.

His mother, the Angela of the book’s title – had become pregnant in New York after ‘a knee-trembler – the act itself done up against a wall’. Four months later, she married Malachy McCourt, her family having pressed him to do the decent thing.

So began a downward spiral into alcohol and poverty, with a feckless father drinking his wages away.

Subjective: Frank McCourt said the memoir chronicled his family and his emotions

Far worse was to come. The death of their daughter at seven weeks sent McCourt’s parents into an abyss of despair, from which they never emerged.

They return, despondent, by boat to Ireland – with Angela pregnant again. But soon, one of the twins, Oliver, has died, too.

His second child’s death precipitated McCourt Sr’s complete decline into alcoholism. He promised coal for the fire, rashers, eggs and tea for a celebration of Oliver’s life, but instead took his week’s dole to the pub.

School, full of bare-footed slum children, is no relief. The masters ‘hit you if you can’t say your name in Irish, if you can’t say the Hail Mary in Irish. If you don’t cry the masters hate you because you’ve made them look weak before the class and they promise themselves the next time they have you up they’ll draw tears or blood or both’.

Then, worse. ‘Six months after Oliver went, we woke on a mean November morning and there was Eugene, cold in the bed beside us.’ He had died of pneumonia.

Another brother is born, Michael – Angela’s sixth pregnancy. As her husband continues to drink away the dole, a friend tells her off for cursing God, saying: ‘Oh, Angela, you could go to Hell for that.’ ‘Aren’t I there already?’ she replies.

Another baby arrives, Alphonsus Joseph. No matter that his family fight for charity vouchers for food, furniture and medicine and share a stinking lavatory with six other houses, McCourt Sr drinks the baby’s christening money.

His father leaves for England, finally abandoning his family. When they are evicted for not paying rent, Angela takes her family to live with a cousin, Laman.

McCourt wrote that his mother and her cousin had an incestuous relationship. ‘She climbs to the loft with Laman’s last mug of tea. There are nights when we hear them grunting, moaning. I think they’re at the excitement up there.’

Laman also beat the children. At 14, McCourt got a job as a telegraph boy. At 19, he left Limerick behind for ever for a new life in America. He first lived in Connecticut, where he became a teacher. He wrote Angela’s Ashes in his mid-60s, and became hugely wealthy.

But how much of his landmark book was true? Did McCourt cross the line between fact and fiction?

Limerick locals, horrified at the squalid depiction of their town, counted a total of ‘117 lies or inaccuracies’ in the 426-page book, that range from obscure details to wrongly accusing one local man of being a Peeping Tom. They called for a boycott of the film of Angela’s Ashes.

Grinding poverty: The film adaptation starred Emily Watson and Robert Carlisle

Grinding poverty: The film adaptation starred Emily Watson and Robert CarlislePaddy Malone, a retired coach driver who appears in the frayed school photograph on the book’s original cover, is among McCourt’s most furious detractors.

He, too, grew up in the Lanes of Limerick and went to the same school as McCourt.

‘I know nothing about literature, but I do know the difference between fact and fiction,’ says Malone. ‘McCourt calls this book a memoir, but it is filled with lies and exaggerations. The McCourts were never that poor. He has some cheek.’

Malone recalls the family having a pleasant green lawn behind their home, and Angela being overweight – despite the graphic descriptions of hunger in the book.

Limerick broadcaster Gerry Hannan spearheaded a campaign against Angela’s Ashes, confronting McCourt on a TV show and calling him a liar.

Although he is too young to remember the period of which McCourt writes, Hannan is convinced McCourt has twisted Limerick’s history to make his book more shocking.

‘As far as I’m concerned, he’s a conman and a hoaxer,’ says Hannan. ‘He knew the right things to say to get the result he wanted. He’s a darling on television. He’s got this beautiful brogue and he can put the charm on. And don’t get me wrong, the book is beautifully written. But it’s not true.’

Their three biggest criticisms of the book, aside from the endless grinding misery it depicts, include the description of a local boy, Willy Harold, as a Peeping Tom who spied on his naked sister. It turns out that Mr Harold, now dead, never had a sister – which McCourt did later acknowledge.

They also disputed McCourt’s account of his sexual relations with Teresa Carmody, when he was 14. She was dying of TB at the time, and locals were outraged that he sullied her memory.

Frank Prendergast, a former Limerick mayor and local historian who grew up within 200 yards of McCourt’s house, says that if McCourt did suffer, it was because he had a feckless father.

‘He suffered a unique poverty because his father was an alcoholic, not because he lived in Limerick,’ says Mr Prendergast. ‘But he has traduced people and institutions that are very dear to Limerick people.’

McCourt said: ‘I can’t get concerned with these things. There are people in Limerick who want to keep these controversies going. I told my own story. I wrote about my situation, my family, my parents, that’s what I experienced and what I felt.

‘Some of them know what it was like. They choose to take offence. In other words, they’re kidding themselves.’

Time will tell whether his impressionistic account of a brutal childhood endures. But whether embellished or not, it certainly left its mark on Limerick – and on literature itself.

Source:

A City Descending Into ‘Ashes’

A City Descending Into ‘Ashes’

By Gerard Hannan

He was known by his childhood friends as Frank ‘The Flay’ McCourt because on his first day at Leamy’s School he was handed a small bun with hard burnt raisins on top. He had never seen a ‘burnt raisin’ in his life and he threw the bun on the floor and danced like a spoilt child on top of it. ‘I ain’t eating that it’s full of fleas,’ he howled as he pounded up and down on the bun. The other hungry boys watched and laughed at the strange behavior of an odd American speaking child who didn’t know the difference between a raisin and a flea. But the name stuck and from that day on he was known as ‘the flay McCourt.’ To this day there are people living in Limerick who don’t know who exactly Frank McCourt is until you tell them he was ‘the flay.’ Invariably they will reply, ‘ah that fellow, sure he was nothing short of a miserable scabby eyed ‘ol snob.’

McCourt himself has something ironic to say about fleas when he writes, ‘the flea sucks the blood from you mornin’ noon an’ night for that’s his nature an’ he can’t help himself.

‘But there is a peculiar mockery about the nickname in the light of the nature of ‘flays’ book,’ says one caller to a late-night radio talkshow in modern downtown Limerick.

He explains, ‘flea by name, flea by nature. A flea will attack you when you are fast asleep and at your most vulnerable. This ‘flay’ called McCourt attacked when other’s were dead.’

In Limerick city, the home of Frank McCourt’s alleged miserable Catholic poverty stricken childhood it is said that everybody loves the author except the people who know him and everybody loves Angela’s Ashes except the people who know the truth.

Since I first became involved in what the international media now describe as the ‘Ashes Debate’ I have been defined as an opportunist, publicity seeker, begrudger, ‘cashier’ on McCourt’s success, plagiarist, a cribber riding on the coattails of Angela’s Ashes, literary social climber and, perhaps most offensive of all, Malachy McCourt publicly described me as a descendant of the lowest orders from the lanes of Limerick. He failed to explain that if I was that then what did that make him but he later apologised and added that bygones should be bygones.

I have spoken to hundreds of journalists from all over the world and I can categorically state that not once did I ever initiate any phonecall, issued no press releases, or made any opening contact with any newspaper, magazine, radio or television station.

In short, if I was guilty of any one of the charges leveled against me then I was doing a very bad job of it indeed. So if I wasn’t making contact with the media about my opinions and feelings on the subject of Frank McCourt and his book then how were they getting my name and number?

The answer to this question came in November 1998 when I received a phonecall from the UK TV company ITV who were producing a special documentary for ‘The South Bank Show’ and wondered if I were willing to be interviewed.

I was surprised to receive the call and asked the researcher where she got my name and private number. Her reply was instant and shocking. ‘It was given to me by Frank McCourt.’

Following from that phonecall I then rang Mary Finnegan who was a researcher for CBS TV’s ’60 Minutes’ for which I had also been interviewed and asked her how she first got my name and number and again her answer surprised me. ‘It was given to our producers by Frank McCourt.’

So if I was ‘guilty’ of exploiting McCourt it was clear that he was a willing participant and was issuing my name ad-hoc to journalists and media folk globally.

This seems totally at odds with a quote he gave to the Daily Mail in January 2000 when he states, ‘I can’t get concerned with these critics, there are people in Limerick who want to keep these controversies going.’ (Amusingly, it can’t be seen as a complete lie as McCourt happened to be in Limerick at the time he gave the quote.) The one observation that kept coming up over and over again was the fact that I was only 40 years of age and was not in the position to speak with any great accuracy about life on the post-war lanes of Limerick.

I believe that any journalist or reporter is only as good as the research he or she is willing to put into any article (you don’t have to be a former inmate of Dachau to report on what life would have been like there when hundreds of people are willing to testify) and I rate myself as an acceptable researcher and reporter of facts.

Apart from this, and more significantly, I always felt that this ‘your too young to know the truth’ observation was completely out of context with the issue at hand. For me, Angela’s Ashes is, and always has been, a bitter, untrue attack on the true spirit of my native city of Limerick which I dearly love. It was a biased book written and ‘designed’ to do maximum damage to the ‘spirit’ of the city and it’s people. In short, Frank McCourt was no authority on that ‘spirit’ because he never experienced it. He existed rather than lived in Limerick for 12 years and buried himself away in the backstreets of the city but he was also a social recluse and an out and out intellectual snob primarily motivated by the desire to ‘get out’ of his hated Limerick and back to his much loved New York as quickly as possible. He had nothing but hatred for the people of Limerick, it’s institutions and beliefs and his book is proof positive of that fact. These pages will prove the veracity of my allegations.

I, on the other hand, have lived in Limerick for over 40 years and this automatically makes me a far better authority on the ‘spirit’ of my city than Frank McCourt will ever be. It’s as simple as that.

Frank McCourt’s bittersweet memoir of growing up poor in Limerick has sold millions of copies worldwide, camped on the New York Times bestsellers list for months on end, won a Pulitzer prize, translated into 25 languages and finally made into a multi-million pound Hollywood movie. It’s crushing story of destitution and human resilience has touched hearts across the world.

But in McCourt’s undesired adopted childhood town, the setting for his memoir, his tales have touched ‘raw nerve’ more than heart and has been attacked as mean-spirited fiction, cruel exaggeration and character assassination. There remains a small but persistent minority who accuse the author of distorting his family’s suffering and humiliation they endured at the hand’s of Limerick’s elite, especially the Roman Catholic clergy and laity. As a boy Frank McCourt ran barefoot in the post-war slums of Limerick rummaging for food and coal for his hard up family.

His home, he claims, was damp ridden and filthy, sewage ran from the outside toilet and there was no knowing where the family’s next meal was to come from.

The controversy was born within weeks of the publication of the book in 1996 when immediate local reaction was to describe it as 426 pages exercising a grudge against Limerick. Many of McCourt’s childhood playmates and neighbours say the book is rife with factual errors, exaggerates the poverty and, most importantly, humiliates his contemporaries by branding them with various sexual transgressions and other so-called sins.

Nowadays, some people in Limerick are utterly fed up with Angela’s Ashes and its story of the McCourt children who lived in the city’s slums (excepting those who died in the family’s communal bed) in the middle of last century. There are those who don’t believe Frank McCourt’s memoir, and those, such as Brendan Halligan, editor of the Limerick Leader, who wish Angela, the Ashes and everyone else would just go away. The book is a ghost haunting modern Limerick life: ‘It overshadows everything.’

Arguments over the veracity of McCourt’s account have, in the year’s since publication, caused endless fuss. The Limerick Leader is well-used to receiving letters that point out flaws in the McCourt children’s saga, and the filming has touched nerves over and over again. ‘Frank McCourt’s book,’ said one Limerick Leader editorial wearily, ‘generated more controversy in Limerick than anything since the opening of the interpretative centre in King John’s Castle. And that was a long time ago.’

The basic geography of the city has changed little since McCourt, who was born in Brooklyn, moved there with his family. The majestic River Shannon splits the city into three clear sections that are tied together by a series of bridges. Georgian brick buildings line the neatly gridded downtown streets. To someone from 1930’s Limerick the character of the city today would be totally unrecognisable. McCourt’s Limerick was poor, wet, malnourished, filthy and miserable. He lived with his parents and three brothers in ‘the lanes,’ the city’s crowded slum district. Consumption and fleas were rampant and the communal toilets overflowed with waste.

But all that is now firmly in the ‘good old days’ and Limerick has risen from the ashes to become a modern, fast moving, thriving small-time metropolis that is not ashamed to openly discuss the sins of her past. Limerick historian and ‘Angela’s Ashes’ tour operator Michael O’Donnell is the first to admit that McCourt’s Limerick is long since dead and those who take the tour will be disappointed if they expect to see lanes, poverty, misery and hardship.

One such ‘tourist’ was Mike Meyer of the Chicago Tribune who was left scratching his head as to why the tour is actually called after the book at all.

He writes, ‘We stood on Arthur’s Quay, a flat green park fronting the Shannon where once stood the lanes, a maze of poverty and damp. O’Donnell raised his voice above the traffic din. ‘Of course, people want to see the Limerick from `Angela’s Ashes,’ but it doesn’t exist. The city has changed so much, and I’m proud of that.’ O’Donnell walked quickly, belying his age of 65. He flicked out a Major cigarette and lit another in one quick motion and led us across the narrow streets.

What followed was a retelling of the Limerick portions of the book in front of sites where it happened. Up Henry Street and past the General Post Office, where O’Donnell smiled his way through a repetition of McCourt’s coupling with Theresa Carmody, wherein they have ‘the excitement.’

O’Donnell led us past the old Dock Road, formerly the setting for picking up stray bits of coal, now the home of a luxury hotel. Mill Lane, where Malachy begged for work, now hosts an office block. Limerick is a clanging, booming town and Dell computers have covered the city’s billboards with messages like, ‘Bored with your job? Join us! No experience necessary.’ The scenes of poverty in ‘Angela’s Ashes,’ O’Donnell noted, had to be filmed in Dublin and Cork. Limerick simply doesn’t have scummy enough sets anymore.

We bustled past kids in Catholic school uniforms to Windmill Street, site of the McCourts’ first Limerick home. The boulevards around it are a sea of To Let/For Sale signs, but O’Donnell took us back by telling some stories about the mattress and fleas and Pa Keating and dying babies. He’s a grand storyteller, Michael O’Donnell is, but I suspect he has better stories to tell than just Frank McCourt’s.

We continued on to Hartstonge Street and Roden Lane and Barrack Hill, and by now O’Donnell had retold most of McCourt’s Limerick life. Dusk broke over the city’s green hills, and we heard about some more of ‘the excitement’ (this time between Angela and Laman Griffin) and then it’s on to St. Joseph’s Church and the St. Vincent De Paul Society and Leamy’s School where the young McCourt was instructed to stock his mind, for it is a palace. O’Donnell paused and pointed to the doorway, ‘Can you imagine? A Pulitzer Prize winner coming from the lanes of Limerick and going to this very school. Why wouldn’t we be proud of him?’

We enjoyed a break at J.M. South’s pub, where McCourt had his first pint, but O’Donnell says he is on the job and sips Coke while I savor a fresh, creamy Guinness. O’Donnell explained that he charges four Irish punts for the tour and that the money goes into the St. Mary’s Integrated Development Program, which funds house painting, hedge cutting and window repairs for the older parishioners. ‘The people of Limerick are still benefiting from `Angela’s Ashes’,’ he said with a smile. Business keeps improving, especially during summer, when O’Donnell leads as many as three walks a day.

The drinking done for now, the two of us walked past the Carnegie Library (now an art museum) and People’s Park, where McCourt had ‘the excitement’ on his own. Youth hostels line Perry Square, facing the neatly manicured fenced-in park lawn. O’Donnell stopped us at Tait’s Clock to tell a story about Peter Tate, tailor to the Confederate Army, and later, having simply dyed the uniforms blue,

Custer’s Seventh Cavalry. ‘Can you imagine, Irish fighting Irish in North America, Irish fighting Indians? We fight everyone,’ he said, and laughed. I’m amazed at the wealth of architecture, monuments and neighborhoods we have walked through, details omitted from McCourt’s narrative, which made Limerick sound like wasteland. Maybe it used to be.’

As the controversy raged on throughout the streets of Limerick it quickly attracted the attention of the world’s journalists and media who flocked to the city to ascertain for themselves why ‘this book’ was being ‘flaked’ by some of the people of Limerick while the world’s intelligentsia continued to sing it’s praises.

It seemed to many people in Limerick that these journalists and reporters were evenly split into two clearly separate groups – firstly, those who loved Angela’s Ashes and it’s author and secondly – those who didn’t. Some came to defend him and prove him right while the others came to ‘exclusively’ reveal that the book was rampant with inconsistencies and that McCourt was the creator of a work of pure and absolute fiction.

Tara Mack of the Washington Post visited Limerick in January 2000 and was charismatic about what she found. ‘An economic boom in Ireland, fueled by subsidies from the European Union and growth in the hi-tech sector, has radically altered the fortunes of Limerick. The city’s economy is thriving. Resident’s, many of whom work at a Dell Computer plant, are confidant and prosperous. O’Connell Street, the main retail thoroughfare downtown, bustles with pedestrians and traffic. The tenements have been torn down.’

New York Times journalist Warren Hoge was not so upbeat. ‘This sodden city in Western Ireland has been such a hard-luck town that it cannot even lay claim to the form of verse everyone assumes was named after it. H.D. Inglis, author of an early travel guide came here in 1834 and found Limerick ‘the very vilest town’ he had ever visited. Heinrich Boll, the German Nobel prize-winning novelist saw it for the first time in 1950 and pronounced it ‘a gloomy little town’ with ‘everything submerged in sour darkness.’ Hoge continues, ‘More recently it has been made fun of in a popular television show as ‘stab city,’ a label – arising out of several muggings in the 1980’s – that the (then) Mayor Frank Leddin, finds so objectionable he will not utter it. Long considered Ireland’s most entrenched Catholic city it has suffered from stereotyping as ‘violent, intolerant, obscurantist and reactionary.’

Paul Daffey writing for the Evening Standard had a different spin on modern Limerick when he reported, ‘Two families were feuding over ascendancy in the drug trade. A member of one family was walking along a footpath when a car sidled up to the kerb. A member of the opposing family jumped out of the car and stabbed the pedestrian in the stomach – with a pitchfork.

The weapon of choice threw a rural twist on an urban tale. It was emblematic of an Ireland that, in the final decades of last century, was wrangling with itself over the shift from rural backwater to urban dynamism. The pitchfork incident could have taken place in Dublin or Cork, maybe even the light-spirited Galway, but somehow this seemed unlikely. Right or wrong, it did suggest merit behind Limerick’s reputation as Stab City. It is a reputation that Limerick hates, largely because it is distasteful, but also because the sobriquet was applied 30 years ago and the city has changed since then.

In the ’70s, the development of high-tech industries and the University of Limerick, which specialises in science and technology, brought a measure of wealth and vitality to the city. But it also created an income gap, with residents of rugged housing estates resenting the new order. Crime and violence were the inevitable result. The rest of the country gained the impression that stabbings were frequent. It titillated some to think of Limerick, with its reputation for inwardness and pious Catholicism, as a bloody frontier.

Violence in Limerick lessened in the ’90s after, among other things, the formation of ‘combat poverty’ groups with funds from the European Union. EU money was also put towards restoration of the town’s fading buildings. The Civic Trust, formed in the late ’80s as the first restoration body in Ireland, was instrumental in giving the worn city a facelift that impressed the rest of the country, although not enough to stop the stabbing slurs and the tittering. Frank Larkin, the public relations officer for Shannon Development, says half the city claims the poverty in Angela’s Ashes is exaggerated. ‘People felt it reflected poorly. They claim they had happy childhood’s and were happy in Limerick. You have that dichotomy of discussion. But there’s certainly a contrast between what Frank McCourt described and today.’

Larkin is unable to put a figure on Angela’s Ashes importance to the city, although he admits it has become a huge selling point. Other attractions include castles, cathedrals, Georgian architecture, the ‘Limerick Expo’ and the International Marching Bands Festival which attracts 40,000 people.

The city’s push – and for that matter Ireland’s push – to improve the poor quality of mid-range restaurants has spawned the International Food Festival, which is held annually, and the Good Food Circle of Restaurants. Limerick might be trying to improve its culinary standing but it has no doubts about its sporting prowess. The city thumps its chest about being Ireland’s sporting capital. It is, at best, a dubious claim, but one that receives support every autumn when Limerick hosts the battles between Munster and touring rugby sides from the Antipodes. Munster, the province that takes in the six counties in Ireland’s south-west, attacks the touring teams with a fervor that inevitably attracts ‘Gael force’ headlines. In 1978, the attack was so effective that Munster defeated New Zealand, a feat that was barely believed across Europe, and less so in New Zealand. The victory remains an Irish side’s only win over the All Blacks and it is not surprising that each player was guaranteed free pints for life.

The city has every right, however, to claim a rich history. Its city charter, drawn up in 1197, is the oldest in the British Isles, which includes Ireland and Britain, and King John’s Castle is a feature of the Heritage Precinct. The castle, built at the beginning of the 13th century, was the stronghold of the British empire in western Ireland and its presence is a reminder of Limerick’s struggles under a hated foreign power. The Heritage Precinct also includes the Castle Lane project, which is the reconstruction of a street from two centuries ago.

Downriver are the docks, which are undergoing a makeover not seen since the Vikings sailed up the Shannon in the ninth century. A handful of pubs in the city centre have also been refurbished. Some are modern and gleaming, but I preferred those with a traditional touch, such as WJ South’s on O’Connell Street. South’s is where Uncle Pa Keating bought the 16-year-old Frank McCourt his first pint. It looks like your average poky Irish pub from the street but opens out generously inside. It was a local for the men from the lanes of Limerick; now the clientele ranges from young professionals to older regulars. The floorboards and decor have been tastefully scrubbed up and Pa Keating would probably wonder where all the sawdust on the floor had gone. The bulldust, though, remains as thick on the ground as ever.

The Limerick banter is fun. Wit and irony are staples and all sentences are delivered with a delightful lilt. The accent is less distinctive than the sing-song carry-on in neighboring Cork but, since the publication of Angela’s Ashes, the language of Limerick is among the most distinctive in the world. Which, if anyone were in any doubt, just goes to show that the pen is mightier than the pitchfork.’

The controversy rapidly gained momentum over a period of two months after the publication of Angela’s Ashes and in that time the so called ‘inconsistencies’ started to emerge. ‘No one in Limerick denies that there was awful poverty in the city in the mid 1900’s, but further investigation has led them to wonder just how poor the McCourts really were. Some people have pointed out how overweight Angela and some of the children were, while the Limerick Leader dug up photographs of McCourt in his boy scout’s uniform. Scouting was expensive and usually for middle-class boys – ‘Is this the picture of misery?,’ asked the newspaper.’

The problem for the pro-McCourt camp is that their man’s mistakes are just the one’s that are likely to cause maximum offence among the people of Limerick, and the guardians of the truth. Queuing at a Limerick book-signing in 1997 was another contemporary from the Limerick Lanes, Willie Harold. Mr. Harold, now dead, appears in the book at his first confession, telling a priest how he has sinned, looking at his sister’s naked body. The problem is, Mr. Harold never had a sister. Many older Limerick people are incensed at the portrait of Angela herself. There’s no doubt that Mrs. McCourt would not like her son’s portrayal. Shortly before she died, in 1981, she was taken to see Frank and brother Malachy perform a stage show about their early lives. She stormed out, shouting: ‘It didn’t happen that way. It’s all a pack of lies.’

Mike Meyer of the Chicago Tribune saw a different Limerick to the one he expected having read Angela’s Ashes when he wrote, ‘Arriving in the city, I walked across the Sarsfield Bridge over the River Shannon. The description of the river was the only passage I remembered from ‘Angela’s Ashes,’ about how Angela could hear the river sing. The water surged quick under my feet, slicing the town in two, running the color of Guinness, all black flow and tan swells. It sang a song of urgency, and the first thought that struck me as I looked at Limerick was: This is a very pretty place.’

He continues, ‘A footpath edged the bank and I followed it west toward the ocean. A pair of swans swam calmly toward me, and past. There were no ashes here, only tranquility and the opposite bank lined with luxury hotels. I asked a few passersby what they thought of ‘Angela’s Ashes’ and about the controversy, but their responses were noncommittal.’

There can be no doubt that Angela’s Ashes has certainly placed Limerick firmly on the international map. The city has rarely attracted so much publicity and for that some of her natives are grateful. However, there are others who don’t believe for a moment that there is any truth whatsoever in the saying there is no such thing as bad publicity. In fact, some would go so far as to say that ‘no publicity’ would be better publicity than the sort of ballyhoo Angela’s Ashes generated for their native city.

Are these people really, as McCourt describes them? ‘Begrudgers.’